Elections 2024: The first phase of the Lok Sabha election 2024 recorded a voter turnout of 69.32%, according to preliminary Election Commission (EC) data. This is approximately the same as 2019, when the first phase saw a turnout of 69.5%. Even the 102 constituencies that voted in the first phase saw a similar turnout in 2019.

However, among the 21 states and Union territories that voted last Friday, there is a vast variation in the turnout, from a high of 84.16% for Lakshadweep to a moderate 49.26% in Bihar.

Nagaland, meanwhile, broke its high-turnout trend this time. Its turnout was recorded at 57.72% amid a boycott call, a sharp fall from the 2019 figure of 83%. In the preceding elections, Nagaland recorded India’s highest turnout, at 87.82% in 2014 and 89.99% in 2009. The northeastern state has been among the handful of regions where the voter turnout has hit these levels. Tripura and Sikkim have been among its frequent companions in this category.

At the other end of the spectrum lie some of India’s biggest states, where the turnout is often paltry (with the exception of West Bengal).

Uttar Pradesh, for example, has ranked among the bottom 5 in the past three Lok Sabha elections, with a turnout of 59.21% in 2019, 58.35% in 2014 and an even more dismal 47.78% in 2009.

Just to emphasise the significance of these figures, over half of UP’s registered voters didn’t cast their votes in 2009, with over 40% giving the polls a miss in the subsequent two editions. UP is India’s most politically significant state, accounting for 80 of the Lok Sabha’s 543 elected MPs.

Maharashtra, which elects 48 MPs, has a similar record, with a voter turnout of 61.02% in 2019 and 60.36% in 2014. State capital Mumbai – also India’s financial capital – is notorious for its low voter turnouts.

According to an April 7 Times of India report, the overall voting percentage in Mumbai, which has six Lok Sabha seats, has risen over 50% only three times since 1991.

But Mumbai is hardly the lone metropolitan city with such a record. National capital Delhi was only slightly better, with a turnout of 60.6% in 2019 and 65.07% in 2014.

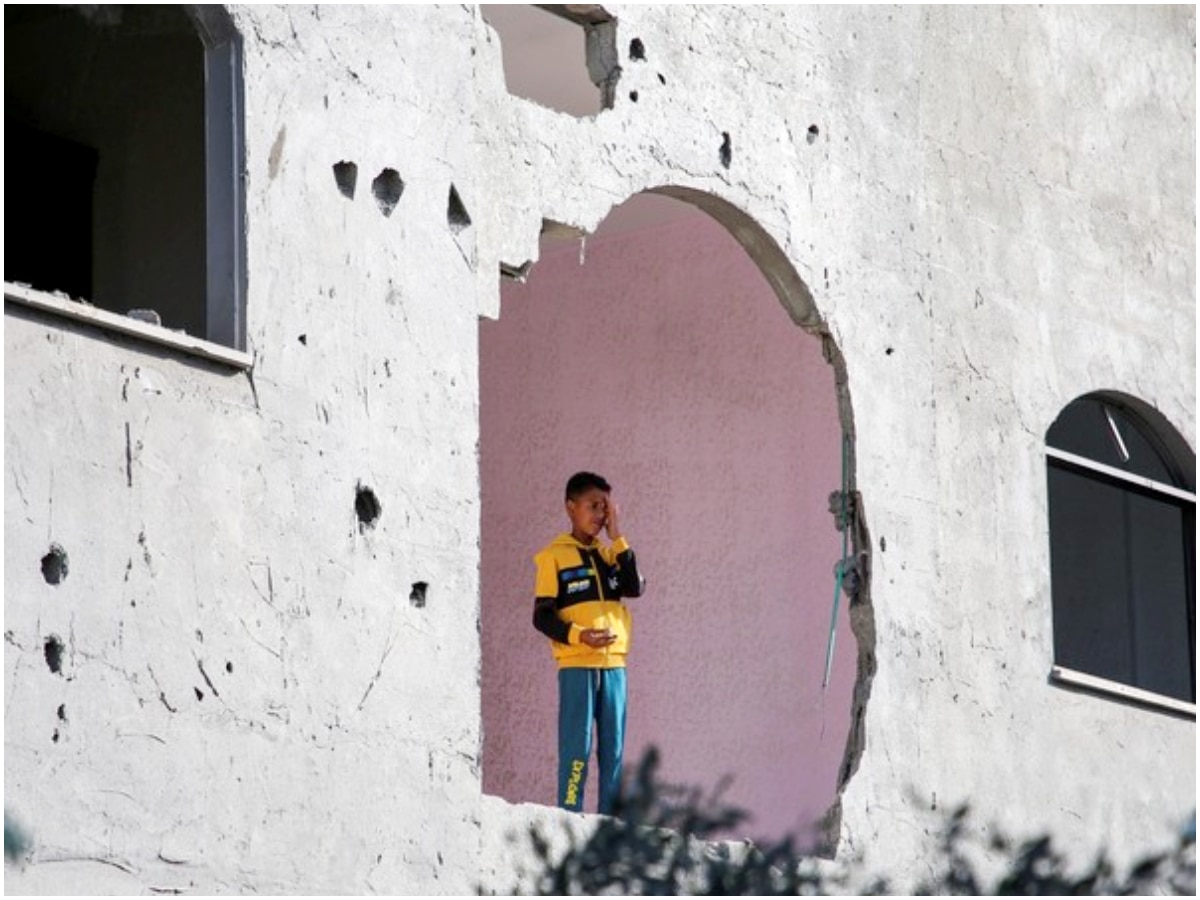

Low turnouts have also been a constant in the political landscape of Jammu & Kashmir – 44.97% in 2019, 49.52% in 2014 and 39.68% in 2009.

The figures vary greatly between the two regions of Jammu and Kashmir – while Jammu has even been known to trump the national average, voter disenchantment, security threats and boycott calls by separatists have hobbled the process in the Valley.

The voter turnout in Ladakh, a part of J&K until 2019 but now a separate Union territory, was also higher than national average in 2019 and 2014.

EC Takes Note

India’s turnout figures have hovered in the neighbourhood of 60% since the first election in 1951-52 (61.16%) – 2019 marked the country’s highest figure ever at 67.40%. The figure was 66.40% in 2014.

The Election Commission (EC) has taken cognisance of the trend of low voter turnouts, and has been working to alleviate the situation. Earlier this month, the poll panel held a meeting with municipal commissioners from major cities and select district election officers (DEOs) from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh “to chart a path towards enhancing voter engagement and participation in identified urban and rural PCs”.

A press release on the meeting — described as a first-ever initiative — sought to explain the scale of the problem by pointing out that “approximately 297 million eligible voters did not vote in the General Elections to Lok Sabha in 2019”.

In 2023, according to a PTI report, the EC told a parliamentary panel that factors driving low turnouts include urban and youth apathy, as well as certain sections’ inability to vote due to internal migration (domestic migration).

ALSO READ | The Missing Nationalism Plank & Muslim Bogey: Understanding The Desperation Of PM Modi

Understanding Voter Turnouts

How exactly voter turnouts affect elections remains a matter of analysis. Some analysts say the figures could be milked for a degree of insight about the mindset of voters, but others disagree.

Speaking to ABPLIVE, psephologist and political commentator Jai Mrug said voter turnouts are indicative of the quality of a country’s democracy. Lower turnouts, he said, point to voter fatigue vis-a-vis the system.

He also noted how an uptick in voter turnout was earlier seen as a mark of anti-incumbency, but has lately been a sign of a decisive mandate.

India’s election data appears to back this assessment. Where the 2004 and 2009 elections saw a voter turnout of 58-60% — the Congress emerged as the single-largest party in both, but short of a majority – the Modi wave in 2014 took the figure to 66.4%, giving India the first majority verdict since 1984.

Asked about the vast variation in voter trends across states, Mrug said voter mobilisation and outreach are easier in homogenous, smaller states like Nagaland and Tripura, but a tougher task in their vaster counterparts that have diverse populations with diverse demands.

He also explained why West Bengal (42 Lok Sabha seats), the lone bigger state notching turnouts of over 80%, is an exception.

“Parties in states like West Bengal and Tripura are extremely proactive with voter mobilisation,” Mrug said, pointing out that this trend is a legacy of the cadre-based system and political activism pioneered by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Parties in these states, he added, have dedicated mobilisation cadres.

Literacy Levels Play A Role

According to journalist and writer Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, voter turnouts have limited impact on an election, and don’t really offer any insight on its outcome.

Asked about the trend of low turnouts, he told ABPLIVE that it could be attributed to the political system and the EC’s failure to do something about the millions of domestic migrants who don’t really have the option to travel back home for voting.

“In urban areas, the trend is driven by apathy,” he added.

Talking about the variations in the figures for different states – after all, even West Bengal accounts for a big chunk of domestic migrants – Mukhopadhyay said higher turnouts in certain regions were a factor of greater political engagement among the population. West Bengal, in particular, has historically had greater political engagement, he added.

Literacy levels, said Mukhopadhyay, also play a role in driving up voter turnouts.

Mukhopadhyay said the EC and the political leaders need to look at concepts like remote voting to ease the exercise for migrants, as well as to eliminate the confusion that often dogs the process of enrolling yourself as a voter in a new constituency.

A proposal to introduce remote voting has been on the EC’s agenda since 2018, a report in The Economic Times noted. But it has met with some opposition from political players.

Concerns raised include the security of the process, the likely difficulties candidates could face in their bid to campaign among the migrant constituents, the logistics of the exercise, and the identification of migrant workers. Doubts have also been expressed about how the Model Code of Conduct would be enforced if the place of residence is not election-bound while a voter’s home constituency is.

In 2023, The Indian Express reported, quoting EC sources, that the panel had “shelved the proposal for now” on account of the political opposition.

Doonited Affiliated: Syndicate News Hunt

This report has been published as part of an auto-generated syndicated wire feed. Except for the headline, the content has not been modified or edited by Doonited